Give me space and time to find... a postmortem of The Coral Labyrinth

Refusal of the summons converts the adventure into its negative. Walled in boredom, hard work, or 'culture,' the subject loses the power of significant affirmative action and becomes a victim to be saved. His flowering world becomes a wasteland of dry stones and his life feels meaningless—even though, like King Minos, he may through titanic effort succeed in building an empire of renown. Whatever house he builds, it will be a house of death: a labyrinth of cyclopean walls to hide from him his Minotaur. All he can do is create new problems for himself and await the gradual approach of his disintegration.

—Joseph Campbell, whom I hate, but occasionally goes hard

The Coral Laybrinth (or just coral.html as it was initially born) was a project I started in March 2020, which probably tells you all you need to know. I was young, out, and in lockdown. Allie X's album Cape God had just shaken my whole conception of reality. I'm sure in the future I'll elaborate to excruciating length on my lockdown experience, but the gist is that after a tumultuous final year of school I'd decided to take a gap year to get my shit together and maybe see the world. By March, however, I'd been spending most of my time sitting alone in my room trying to write. I'm sure you can imagine the surrealness of waking up one week to find the whole world trapped in the same hell.

Like all the others, I was bored of being bored, so I made my own game. I settled into a rhythm for most of the year: each day that I had nothing to do, I'd work on two projects, which usually meant I'd add a passage or two to coral.html in the morning and type a few lines into my long-term novel project after lunch.

I assumed my efforts, when they eventually bore fruit, would either be universally celebrated or completely ignored. Well, my labyrinth has ended up much more the latter than the former, although it's still the longest (largest?) piece I've released. Meanwhile, many reimaginings later, my novel still remains incomplete. So what is there to learn?

Only Daedalus could've thought of this

The approach I had to developing this project is more of its statement than anything that actually happens in the game. I'd gotten fed up with working on projects that had plot structures and planning and that I'd spend a lot of time on but never seem to make it any closer to completion. As an antidote, I came up with a project that would always essentially be finished: it could be abandoned or expanded at any time.

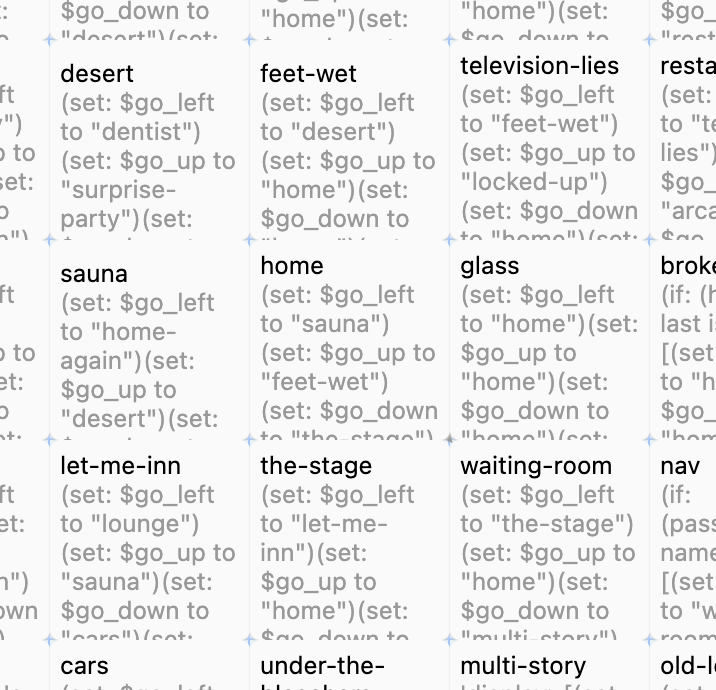

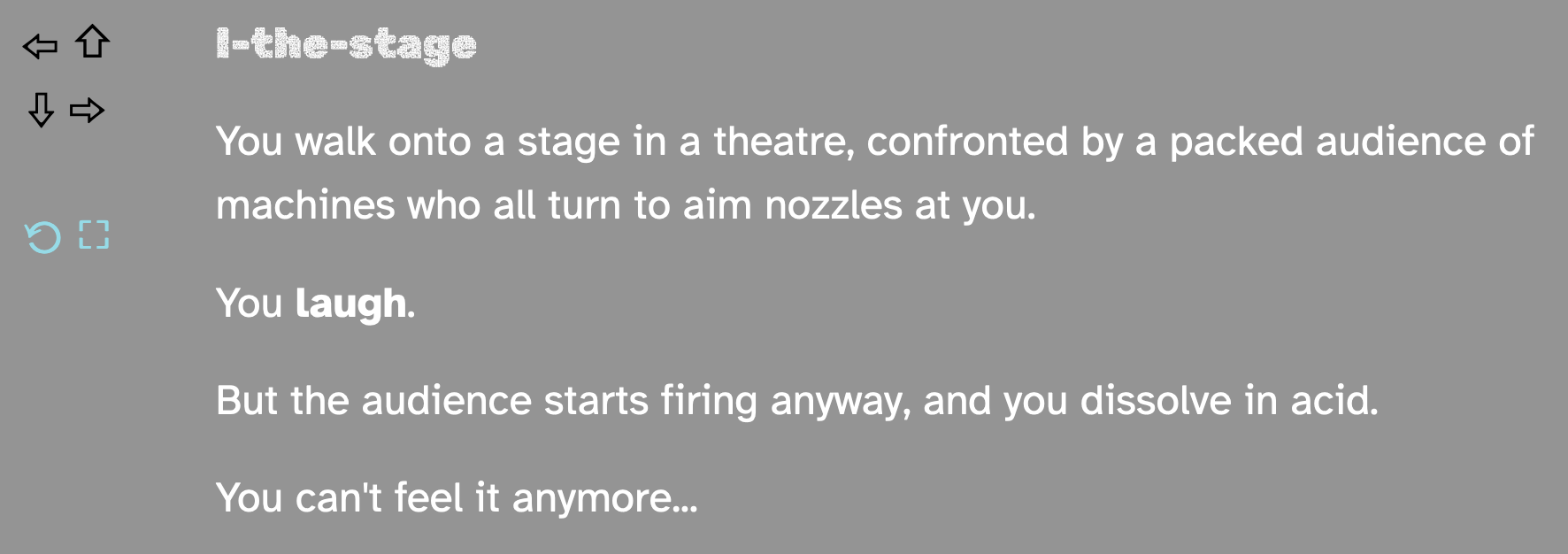

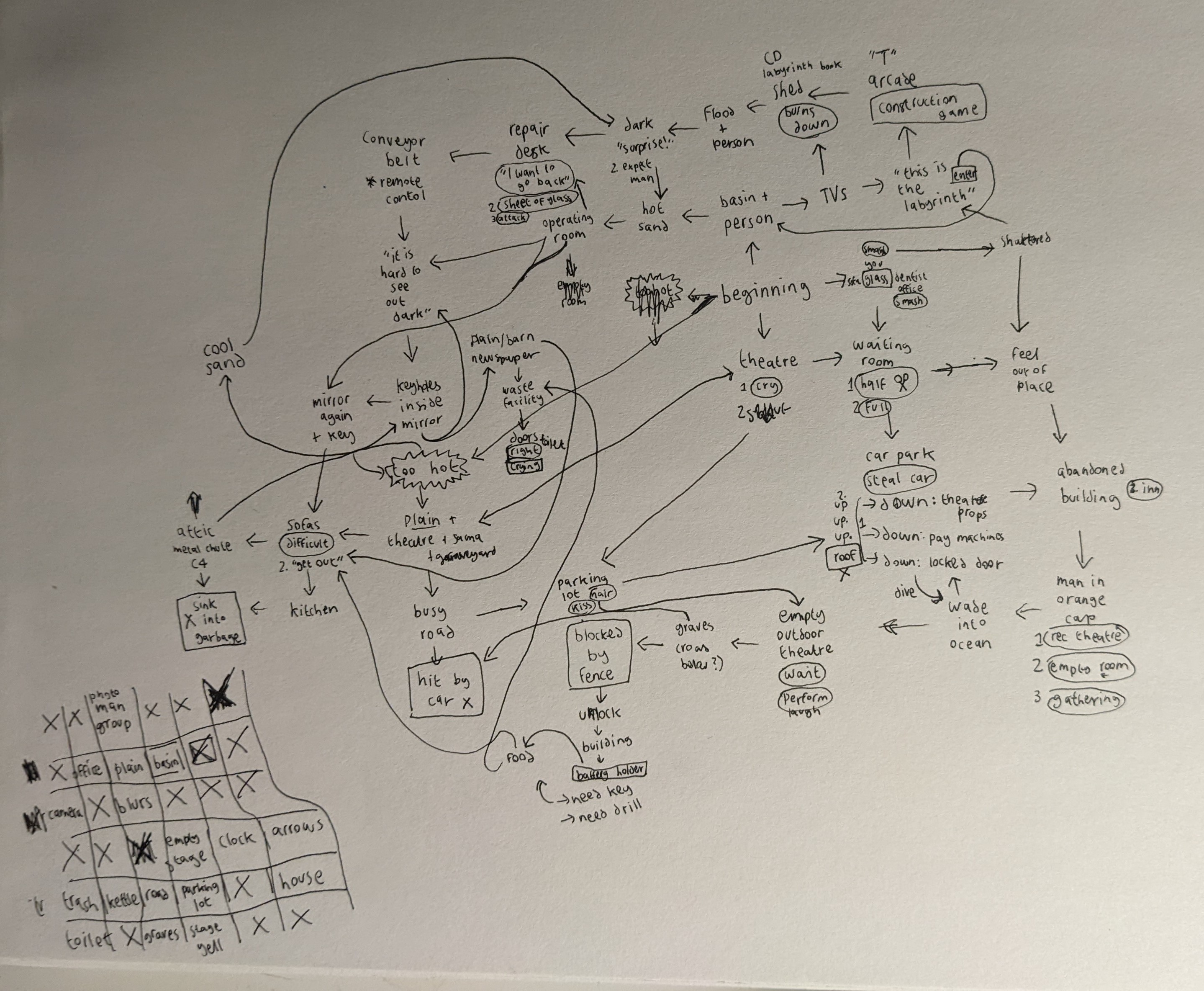

In the beginning, I made one passage, which contained the brief room description and a 'puzzle' requiring the player to click a link and pick up a key which then unlocks the compass navigation used to explore the rest of the game. It's a silent tutorial: at first there is only one link, so you learn to interact with the main passage, and then your attention is drawn to the navigation, so you find out how to continue when you're bored. And yes, this is a Twine game based around moving in compass directions. Logically, I should've made this a parser game, but that wasn't the point. The point was to figure out what I could do with Twine. I later tried to recreate the game in Inform 7, but that just exposed how deeply tied this project was to the medium of Twine Harlowe: just getting a simulation of that initial single-link puzzle to work took hours and still wasn't bug-free. A parser Labyrinth would have to be its own thing, not a port of this project, so this will always be the labyrinth I made.

I followed two rules after that initial passage:

- Each passage must be added next to an existing passage (so the layout of passages in the Twine editor matches the layout of the in-game world the player is traversing).

- Each passage must embody a unique gameplay concept.

That was it. Unlike basically anything I'd tried to make before, I had no overarching concept or plot I was trying to reach. I figured those might emerge, but the point would never be how it ended. I wanted to explore and experiment, so I made a game in which players would find themselves doing the same.

Key features for both the story and gameplay often arose from quirks of the engine: most notably, it isn't possible to return to a passage that has already been visited without resetting the game (except, of course, for the one passage whose unique gimmick is being revisitable). Traversing the game is almost like Snake, since 'runs' are generally short and end in death or winding up in a room with no exits (because you've already visited all its neighbours). This wasn't planned from the start, but came about because I felt it was a simpler solution than having to either write lots of extra (and potentially bug- and oversight-prone) text and code to account for the possibility of players revisiting previous passages, or to accept the confusion of endless continuity errors. This wouldn't have happened if I'd made this a parser, but I'd also have been able to write substantially fewer rooms.

The result became crucial to how the game is played: it's impossible to end up going in circles around the same few passages, which should keep it feeling fresh. There's no continuity between runs, which also suited my game design sensiblities: I had to make the material sprawling enough to be interesting for both first-time players and people on their hundredth reset, giving it an arcadey feel which tied progress to knowledge, experience, and notetaking rather than timewasting arbitrary checkpoints, while also being an extremely unarcadey sort of game.

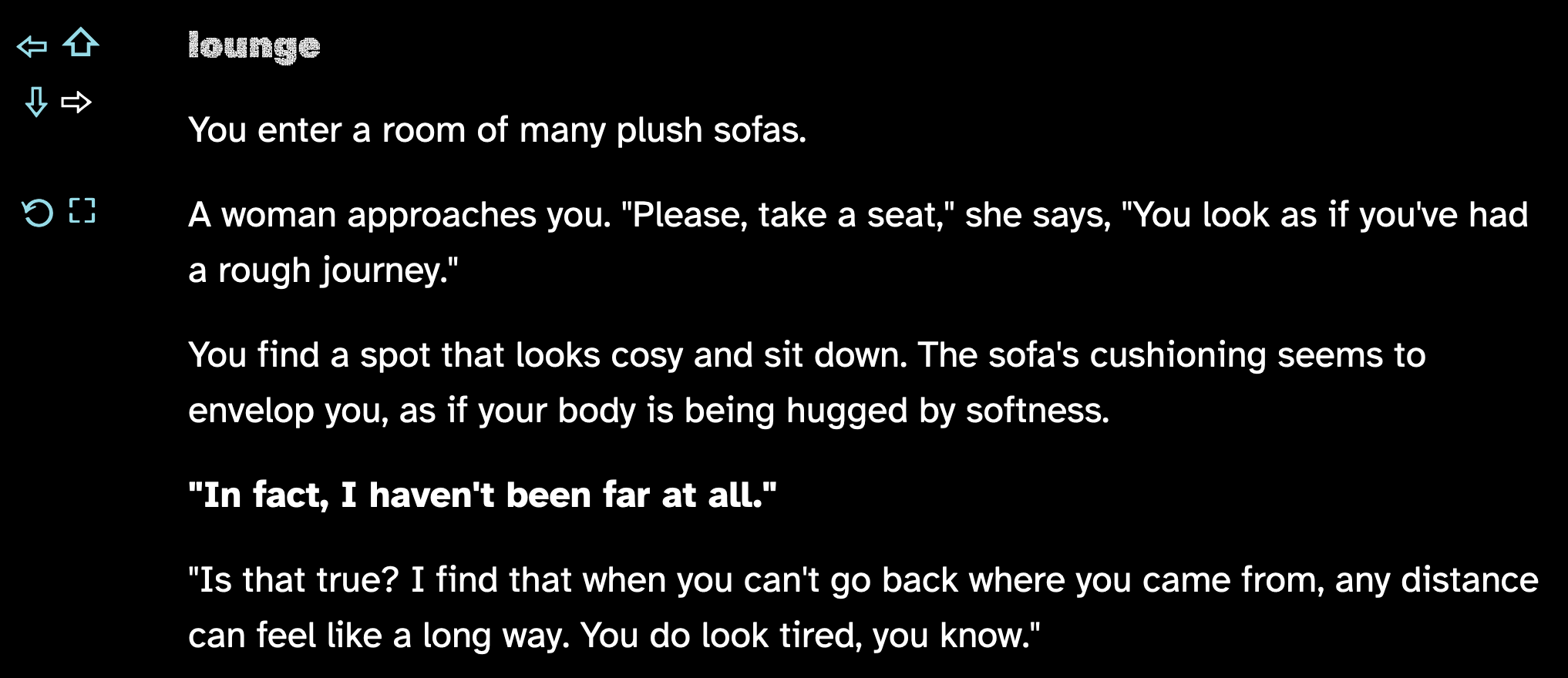

Must be lonely loving someone trying to find their way out of a maze

Eventually, as I'd hoped, there was an overall premise and concept, one that the player was meant to gradually discover at the same pace I had. The Coral Labyrinth is a surreal society composed of a network of "homes", several of which are occupied by nameless people referred to by appearance or role (the innkeeper, the neighbour, the director, etc.). You are a new arrival to this community, and the inhabitants are friendly if uninterested in introducing you to their traditions. This is not a hostile world, but it isn't always safe to traverse; I hoped to write a game which might be relaxing to play but didn't fall into the uncomfortable denialism of being 'comforting' or 'reassuring'. There are puzzles, but they're not especially stimulating, which might be the element with which I'm most dissatisfied. Mostly they involve finding the right objects or the right route to transport an object to the right place, with a little bit of ingenuity required to figure out what I'm implying.

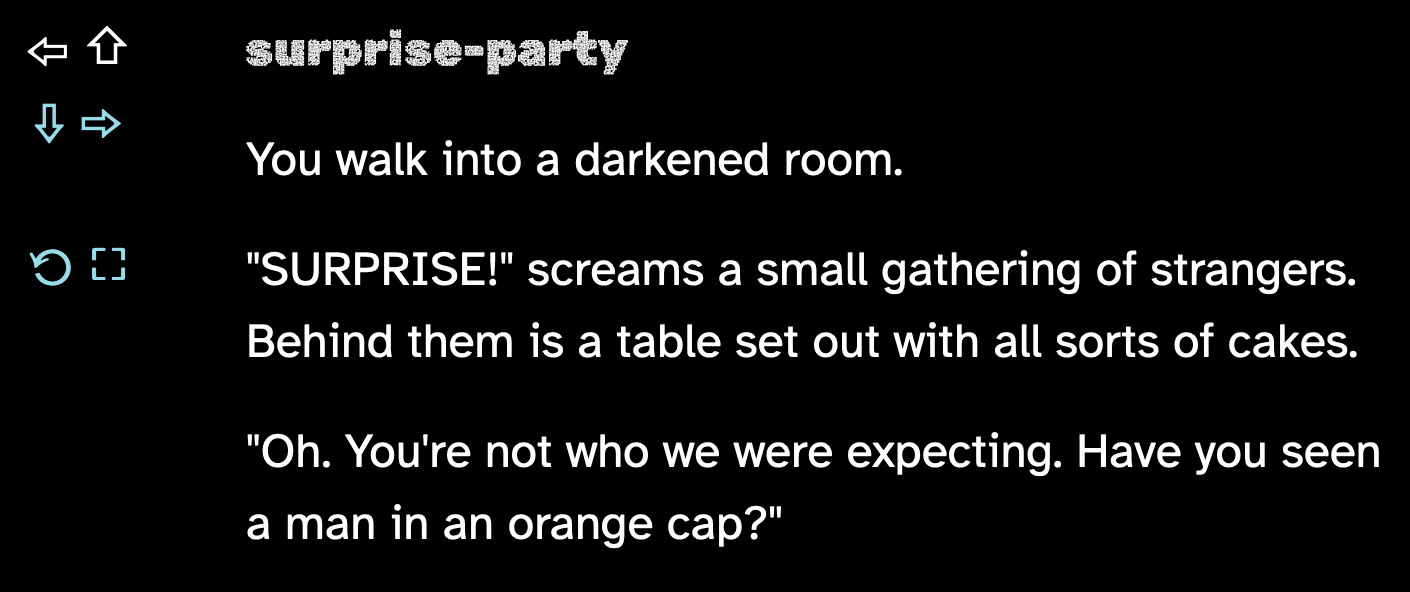

In one slightly more complex example, you might meet a charming if irritable innkeeper and have her serve you a cup of tea, and then in another part of the map encounter an old man living next to an abandoned inn who shares a memory of a boy who lived there and was his childhood friend. If you can think like me and have the patience to keep reloading, you might be able to deduce that the innkeeper moved home and transitioned, and direct the old man to reunite with her (or, alternately, to arrive at his surprise birthday party on the other end of the labyrinth).

The game does have an ending, but probably not the one you're expecting. I knew that most people, when thrown into a labyrinth with no instructions, would assume their goal is to find a way out. But the real goal in this game is to learn that finding a way out is not the goal. This was another thing that sort of just came up by instinct and I only later realised was kind of a defining feature of the experience; I'm not sure anything in the game actually discusses the idea of a way out. (To emphasise how little it crosses my mind, I didn't even mention this concept in the first version of this post!) There's a room very close to the start called "desert" which people have interpreted as a false ending, since it's described as an open space, but is actually still contained within the labyrinth. (The desert's actual gimmick is that it's described as either cool or hot depending on whether you enter it from the sauna or not.) But there isn't actually any way to leave. The labyrinth is the whole world. That's why it's a labyrinth, not a maze: because there is no wrong path.

A nightmare where I'm trying to find you in a maze with no staircase

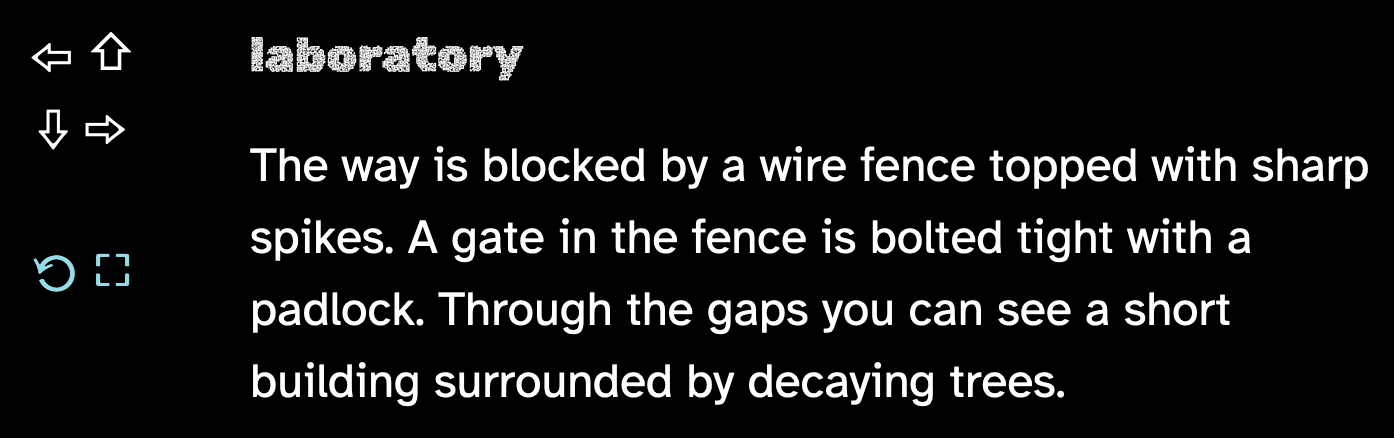

So what's the actual ending? I won't tell you how to exactly how to make it there, but I will tell you what happens, since I don't think anybody actually has reached the end. As you explore further, you might find hints about an incident occurring at a laboratory, which you may eventually discover in a distant corner of the map. It's designed to be at the farthest point from, with many obstacles around it that should make it difficult to encounter until you've already seen most of the rooms. Unlike most of the spaces in the labyrinth, it's described as having hella ominous vibes.

The goal of the endgame is to break into the laboratory. A variety of items collected from other passages are needed to achieve this goal, although there are multiple accepted combinations (and entrypoints). It's probably still too difficult, since it was built on two kinda conflicting hopes:

- that a player would only be able to enter the laboratory after spending many runs mapping out the labyrinth, thus being able to plan out a route to get all the items they need;

- that a player would only find the laboratory at the end of a long run, thus being likely to have unknowingly brought all the items they need to win, or at least to get far enough to have a good idea of where to go next time.

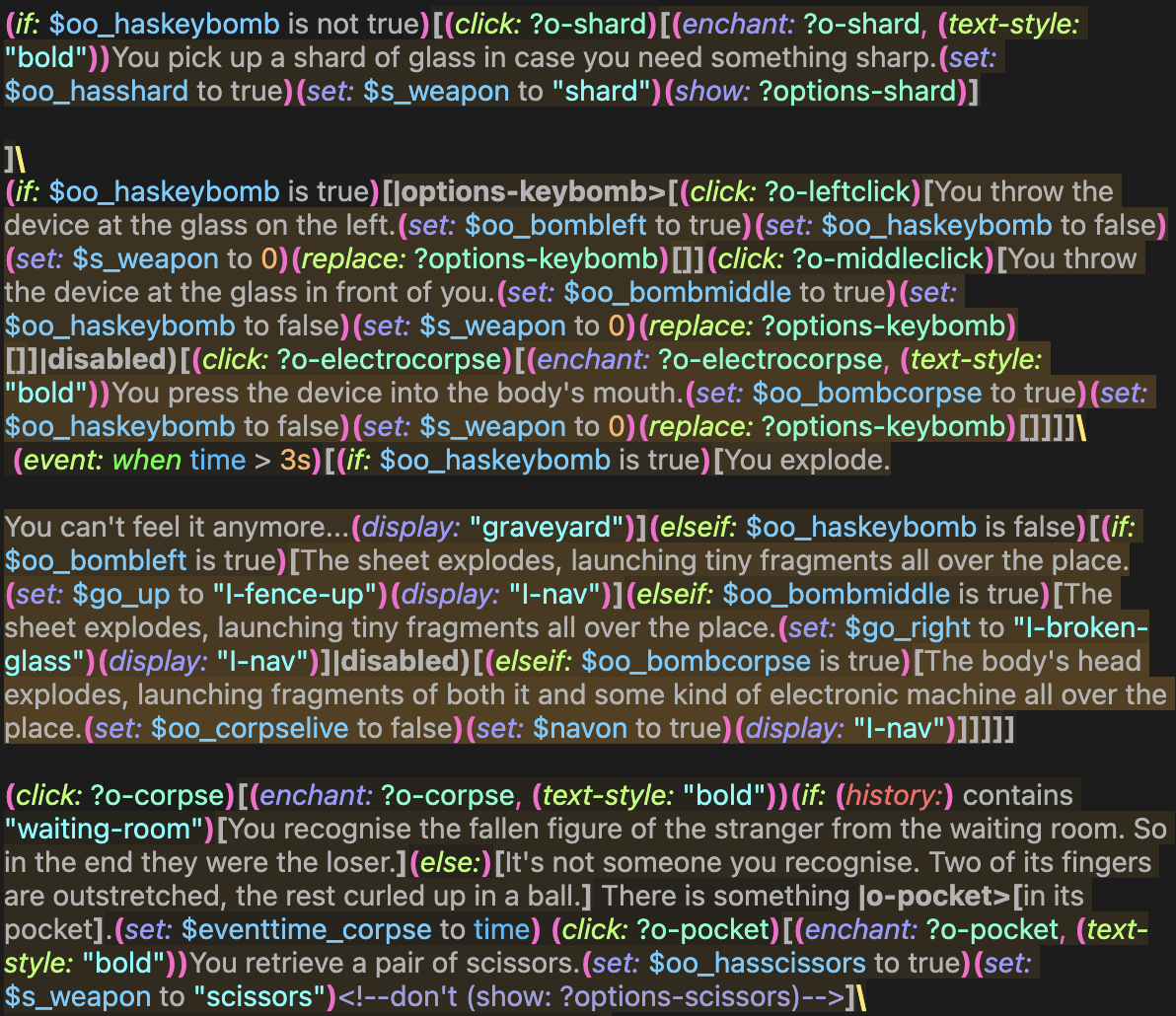

Once you're in the laboratory, you'll find a machine which may or may not electrocute you and instantly end your run depending on your past and present actions. (I figured anyone who's made it this far is familiar enough with the game to not be put off by surprise bullshit. This is similar to how if I were to arrive on time to a function, I would wait outside for a few minutes to make sure that nobody gets the impression that I am capable of punctuality.) If you manage to activate the machine, you'll get to choose from new sidebar buttons resembling audio controls. Pause and stop are gags which freeze or end the game, but fast forward takes you to the next phase..!

After the screen stutters and breaks down (an effect I discovered as a glitch resulting from trying to use Harlowe's own macros to set the colour of the page background), you are returned to the initial empty room (which you'll realise is considered your home if you pay attention; I originally intended to let you bring objects there as decoration, but this stopped making sense after I added the no-backtracking constraint). Except the room is a wreck, and the labyrinth is now invaded by murderous monsters. (I couldn't decide whether the enemies would be aliens, zombies, or robots, so I settled on alien zombie robots.)

You can explore the adjacent rooms and attempt to solve time-sensitive puzzles to disarm the robots and gain weapons you can use to fight back. At long last, you can have a second conversation with the old person in the water room, except he is also trying to kill you, because he thinks you're one of the invaders. (Decide for yourself what that might mean.)

All that is to say, if anyone did manage to spend enough time learning the labyrinth to actually beat the first phase, they would almost certainly be rewarded by immediately getting killed and sent all the way back to the start. (Ideally, they'd only be sent back to the beginning of the second phase, but I didn't get that far. At least, there isn't a save-state feature implemented in the online version, but maybe it got lost.) If they persisted long enough to make it past the first robots, they would reach the unceremonious end of the game, because that's where I decided to stop, at least for this "demo." (There is actually a second 'ending' within the first phase, or 'ending' in the sense that it's meant to lead to a whole nother area I didn't implement.) Maybe it's lucky no-one invested too much time in this one. (Maybe I have a cruel sense of humour...)

Turn back from this cave

So, yes, this is a game which is always finished and can't get out of hand... and it's also yet another game which got too ambitious and will always remain unfinished. The idea was that each phase would introduce a new universal mechanic, and feature the same maze and characters at a different point in time.

If the player and the other characters failed to stop the invasion, then the next phase would've seen the peaceful labyrinth transformed into a capitalist hell. A currency mechanic would be added, and the player would have to gather and spend money to do things they'd previously been able to do for free, while watching the other residents become increasingly weary, desperate, and violent. Conversely, if you won the invasion phase, then the characters would decide to form a government in the hopes of defending against any future attacks. The next phase would probably be a revolution or whatever, and then we'd see the next generation, until eventually the community became a deserted ruin. You'd also be able to go back in time and see how the labyrinth was originally built, so it would all be nice 'n' cyclical.

And I still think this is a cool structure, but... maybe it's better suited to a game that's a little less sprawling in scope. (My wants right now: I want to make a piece with a real rhythm to it, and I want to make a piece that has interesting mechanics. (Don't) Save Me is the only piece I've written since that is actually a 'game' in the sense of involving win conditions, but it still suffers from being basically impossible to solve unless you're relentless or lucky—it's just in that case I managed to make that the point, and being good at the game has no effect on the end results.)

There's a few reasons I could give for why it ends where it does:

- Lockdown was over, and I wanted to move on.

- I'd filled out a nice neat 6x6 grid of passages, which felt like an appropriate stopping point.

- I'd tried to add a few more passages, but screwed up and managed to delete that evening's progress instead of an older copy, which left me very frustrated and reluctant to continue working on the project. I did write down all the changes I could remember making, and eventually reimplemented "restaurant" in time for the public release. (Also, wait, doesn't Twine have a backup feature? Maybe not at that time.)

- Due to the one-passage-at-a-time nature of the game's development, I never bothered to implement a proper inventory system. All the objects that can be collected are simply tracked using their own individual boolean variables! This was already getting unwieldy by the end of phase one, but meant that there really wasn't much progress I could make on the invasion phase since I wanted it to revolve around the mechanic of the player being able to collect and switch between various items to use as weapons. Reworking the inventory system would require a huge amount of changes to the existing passages. Doable, but could I be bothered?

- The premise of the project became untenable.

Despite beginning development in early 2020, it took until April 2023 before I actually released the game in public. I can't really account for why it took so long; according to the ingame changelog (an easter egg in the "arcade" home), I first considered the game to be 'complete' in November 2020, which would've been at the end of my disastrous first attempt at going to university. Maybe I was waiting to find people willing to playtest, maybe I wanted to add more polish, or maybe I was nervous and distracted and no longer saw a point in release.

Lost in the labyrinth of my mind

You may have realised the problem: I made a game which is exactly the kind of game I wanted to play, except that I am the only person who cannot play it the way it is meant to be played. This is a game about exploring the unknown, but I built this labyrinth, so I already know all that there is to find. What do you do once you've finished mapping your own mind?

Well, that suggests the real game was the game that I did play: the one about the relationship between me, Leon Arnott and Chris Klimas' programming system/environment, and my hypothetical audience. I wanted players to get to experience the same feeling I did as they explored the strange prison I'd designed. I corralled a few friends into testing it out, and their feedback helped; after much deliberation I decided to have the internal codename for each passage displayed ingame to reduce confusion about rooms which have multiple variants depending on which direction you enter. (Though I also just love the idea of giving each screen a quirky caption like in VVVVVV or I Am Easy to Find. Actually, that's what I want to make: a piece which could implausibly be described as 'VVVVVV meets I Am Easy to Find'!) But there never developed a community or any serious efforts to uncover the mysteries of the labyrinth. This is a long post, and it probably feels like I've given a lot away, but there's still so many more little moments left to see.

To be fair, it would be super easy to just download the game, crack it open in Twine, and cheat, though the often dense and tangled code might act as a deterrant. But still, it's another quirk of the format (and our current culture) that unspoiled exploration is forced to be more of a solo endeavour.

Caught up in the maze of love

A brief covid scare earlier this year suddenly plunged me back into a mindset I didn't know I still retained. I had visions of locking myself in my room, putting on Ada Rook or Liv.e, and going back to work on the labyrinth for a couple of weeks. But then my test came back negative and I continued moving on with my life.

I still love this game, and it definitely served its purposes of teaching me the mechanics of Harlowe (and interactive fiction as a whole) and getting me out of the gutter of overambition to actually accomplish a task. While I haven't done anything quite like this since, (Don't) Save Me and Sleepless were written with a similar rhizomatic approach: I started with a rough idea of a core sequence of events, but allowed myself the freedom to add (or not to add) additional tendrils and branches anywhere they felt right.

I think it's an interesting way to make use of interactive fiction's unique properties. First because these rambles being optional means readers aren't getting bored waiting for the plot to continue, and second because it allows for the fun and interestingness of taking a single premise and just doing each possible variation on it until you're bored or exhausted. Maybe we could think of it as the Just a Minute technique: write about a subject for as long as you can without hesitation, repetition, or deviation. Eventually, you still have to stop.

I remember later in 2020 hurrying in the rain to buy a copy of Sufjan Stevens' The Ascension on the day before we went back into lockdown, then listening to that album while reading Susanne Clarke's Piranesi, another story about an unusual life in an unusual labyrinth. But—for the first and last time you'll hear me say this—Campbell kind of has a point. As much fun as it was to explore the strange world of Piranesi, I found myself much more interested in what would happen to the protagonist once they inevitably returned to conventional reality, and disappointed when this turned out to be treated as little more than an epilogue.

The Coral Labyrinth was a lot of fun to write, but carrying on would mean I'd just keep going nowhere. 'Write what you want to read' is good advice, but in the end, if you're not writing for anyone but yourself, you can only really write one story.

At some point, I did have to leave the labyrinth, and find out what was waiting for me out in the world of other people.

Next: (Don't) Save Me.

The Coral Labyrinth

You find yourself in an empty room.

| Status | Prototype |

| Author | Coral Nulla |

| Genre | Adventure, Puzzle |

| Tags | Exploration, maze, Text based |

| Languages | English |

Leave a comment

Log in with itch.io to leave a comment.